Former Gov. John Bel Edwards announced on Monday that he will not run for the U.S. Senate in 2026, ending months of speculation that had frozen the Democratic field and leaving the party with a steep uphill climb in one of the nation’s most conservative states.

After giving it careful consideration, we have decided that now is not the right time to re-enter public office. After eight years in the Governor’s Office, and with two grandbabies at home, we’re committed to being the best Papa and Nonna we can be. #lasen #lagov

— John Bel Edwards (@JohnBelEdwards) October 13, 2025

In a statement on X, Edwards said he and his wife, Donna, “have decided that now is not the right time to re-enter public office,” citing a desire to focus on their family. Edwards, who served two terms as governor from 2016 to 2024, framed his departure from politics as a personal choice — but the political ripple effects are immediate and significant.

For months, Democratic donors and operatives in Louisiana have quietly expressed frustration that Edwards’ indecision kept the party from coalescing around another contender. Several potential candidates, including sitting and former elected officials, were reluctant to begin raising money or building statewide infrastructure for fear of being sidelined if Edwards entered the race late.

“He was the only Democrat with the name recognition, the fundraising base, and the cross-party appeal to make the race competitive,” said one longtime Baton Rouge strategist. “But the delay cost us valuable time. Now, whoever runs has to start months behind Republican candidates who’ve been campaigning since spring.”

A New Political Landscape

This race marks the first U.S. Senate contest since Louisiana ended its unique “jungle primary” system. Under new rules pushed through by Gov. Jeff Landry and the Republican-controlled Legislature, the state will hold closed party primaries for the first time in decades.

That means Democratic and Republican candidates will compete within their own parties in April before advancing to a November general election — more like the systems used in most other states. The change, widely viewed as a strategic advantage for Republicans, makes it harder for Democrats to capitalize on low-turnout, multi-candidate races where crossover votes sometimes helped moderates advance.

“It’s an entirely new game,” said 2024 Democratic congressional candidate Quentin Anthony Anderson. “The old jungle primary gave Democrats at least a theoretical shot if Republicans split the vote. In a closed system, there’s no such path. You have to build real party infrastructure and motivate Democratic turnout—two things the state party hasn’t done effectively in years.”

Understanding Louisiana’s New Primary Rules

Key features as currently codified:

-

The switch applies to specific offices: U.S. Senate, U.S. House, Louisiana Supreme Court, Public Service Commission, and BESE.

-

In those races, primary ballots will list only candidates from the voter’s party (Democratic or Republican).

-

“No Party” (unaffiliated) voters may choose which party’s primary ballot to vote in (Democratic or Republican) in those elections—but once they do, they must stick with that party’s primary through any runoff.

-

The earlier “open all-party” model (jungle primary) remains in effect for many state, parish, and municipal offices that are not covered by the new law.

-

As part of the transition, the Independent Party was officially dissolved, and roughly 150,000 former Independent Party registrants were moved to “No Party” status.

Under the new schedule, the party primaries for Senate and other covered offices will be held April 18, 2026.

In practical terms, this changes the calculus for Democrats:

-

They can no longer count on a multi-party scramble or vote-splitting among Republicans to open pathways.

-

Mobilizing registered Democrats and “No Party” voters who commit to the party ballot becomes essential.

-

Voter confusion may be high — some electors may not understand which ballots they can (or must) receive.

In short: the new regime raises the stakes on base turnout, early infrastructure, and clarity about registration.

The Republican Landscape: Money, Momentum, and Messaging

While Democrats were waiting on Edwards, Republican candidates have been moving full speed ahead. State Treasurer John Fleming, State Sen. Blake Miguez, and Public Service Commissioner Eric Skrmetta have all announced campaigns challenging incumbent Sen. Bill Cassidy, who faces backlash from conservatives over his 2021 vote to convict Donald Trump in the Senate impeachment trial.

Cassidy’s vulnerability on the right has led to an unusually competitive GOP primary, but none of that necessarily benefits Democrats — especially without a marquee name like Edwards to rally donors and energize moderate voters.

With Edwards out, the Republican side is already well ahead in many respects. According to FEC and public campaign data:

-

Cassidy, the incumbent, has raised approximately $9.29 million, with $8.74 million cash on hand as of mid-2025.

-

Fleming has raised $4.4 million and holds over $2.1 million cash on hand.

-

Miguez has raised about $1.82 million with nearly all in cash assets.

These numbers give GOP candidates a head start in deploying staff, media buy, and infrastructure — advantages Democrats must now surmount.

Cassidy’s vote to convict Donald Trump in the second impeachment remains a vulnerability. Miguez and others are already attacking him on that ground.

Prospective Democratic Entrants: Hopefuls and Hurdles

Without Edwards, the Democratic field is wide open — but no candidate currently combines all the qualities (name recognition, fundraising, electability, and base trust). Below are key names being discussed, along with their strengths and headwinds:

Gary Chambers Jr.

Gary Chambers Jr.

-

Strengths: He has statewide recognition, especially among younger progressives, and a flair for media visibility.

-

Headwinds: His polarizing reputation poses risk, especially in a climate where Republicans will eagerly inject cultural and identity issues. Some Democrats question whether his past campaigns prioritized exposure over building a durable statewide political operation.

Mitch Landrieu

Mitch Landrieu

-

Strengths: Landrieu has successfully run for statewide office (as lieutenant governor) and most recently served as New Orleans mayor, giving him broader brand and fundraising reach. He also retains national and institutional connections from his time as an adviser to former President Joe Biden.

-

Headwinds: Ties to the federal establishment and elites may be framed negatively, especially in more rural, anti-Washington parts of the state. He may be vulnerable to being painted as too connected to the Biden White House at a time when Biden’s standing & legacy among Democrats is still extremely polarizing.

Cleo Fields

Cleo Fields

-

Strengths: Fields currently holds a U.S. House seat in the 6th District. He has existing federal relationships and statewide name recognition due to his lengthy political career.

-

Headwinds: He carries significant political baggage. Many Democrats have criticized his actions in prior cycles — especially claims he made deals with Republican Gov. Jeff Landry’s team in 2023 to undercut Democratic candidate Shawn Wilson‘s campaign and benefit from redistricting, as well as his well-documented involvement in the Edwin Edwards casino license scandal that sent the former governor to federal prison. That history may make him a hard sell for parts of the base.

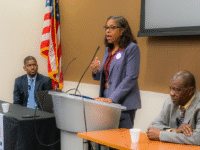

Ashley Shelton

Ashley Shelton

-

Strengths: Shelton leads the Power Coalition, which has mobilization capacity and networks across parishes. Her connections with civic groups and on-the-ground organizing are real assets.

-

Headwinds: She is less known electorally and lacks a proven track record in campaign fundraising, public messaging, and statewide electoral operations. Transitioning from civic activism to high-stakes politics carries risk.

Davante Lewis

Davante Lewis

-

Strengths: Lewis is viewed as an emerging voice with energy and appeal among progressive and younger demographics — something the party needs.

-

Headwinds: He has made statements in the past that could draw Republican opposition targeting. Additionally, as the state’s highest-ranking LGBTQ elected official, he may face resistance in more socially conservative parishes. He will have to establish credibility quickly in areas where he is less known.

Julius Alsandor

Julius Alsandor

-

Strengths: As mayor of Opelousas, Alsandor has executive experience. He is seen as having good relationships within the state Democratic apparatus, and his moderate posture may help bridge internal divides.

-

Headwinds: His statewide name recognition is low. His fundraising networks are not yet proven at scale beyond his region. He would face an uphill climb just to be seen, much less competitive.

Kaitlyn Joshua

Kaitlyn Joshua

-

Strengths: Joshua is a former organizer with the Power Coalition and has already demonstrated a national voice — she spoke at the 2024 Democratic National Convention on her personal experience under Louisiana’s abortion laws. She also is a co-founder of Abortion in America and has grassroots organizing credentials in reproductive justice and environmental causes.

-

Vulnerabilities: Unlike candidates with prior electoral office experience, Joshua would be relatively untested in competitive statewide campaigns. She lacks name recognition in many parts of the state. Her strong identification with reproductive rights advocacy could also make her an early target in a Senate campaign — Republicans are likely to cast her as a “single-issue” candidate to suppress crossover and moderate support.

Ted James

Ted James

-

Strengths: Former state representative (2012–2022) and recent regional administrator for the U.S. SBA, James brings both legislative and federal experience. He also ran for mayor-president of East Baton Rouge Parish in 2024, giving him higher visibility and a recent campaign apparatus.

-

Vulnerabilities: In the 2024 mayoral contest, James placed third in the primary and did not advance, which some Democrats say contributed to splitting votes and facilitating the election of Republican Sid Edwards. His absence from electoral office since then means he would need to rebuild statewide networks quickly.

It’s possible a coalition forms early around one of them, but the longer the decision is delayed, the more difficult it becomes to catch up with Republican money and messaging.

What’s Next for Democrats and the Party

The Edwards announcement resets the race—but not in the Democrats’ favor. Key dynamics now include:

-

Damage control

The party must quickly land on a nominee and begin closing the organizational and financial gap. That means mobilizing donors, institutional players, and voters who sat on the sidelines believing Edwards would run. -

Registration urgency

Because of the closed-party primary system, voters must belong to—or commit to—a specific party primary. Efforts to ensure people register (or switch) appropriately will be critical. -

Messaging wars

Republicans already have weeks of claim-making. The Democratic nominee must quickly clarify their narrative before being boxed into reactive space. -

Turnout risk

Efforts to rouse turnout, especially in Black, rural, and smaller parishes, will make or break any Democratic chance. The nominee must mount serious ground operations far faster than typical in previous cycles.

In many ways, Edwards’ withdrawal is more than a lost opportunity — it’s a forced reality check. The Democratic side no longer walks into a race with a presumed standard-bearer. Whoever steps up now must grapple with financial deficits, organizational gaps, and a compressed runway. The path is steeper, but not necessarily impassable — if they move decisively.

Edwards’ parting words — urging voters to “reject extremist politicians” and lamenting the country’s direction — may sound like a call to arms. But without him in the race, Louisiana Democrats are left searching for someone willing and able to answer it.