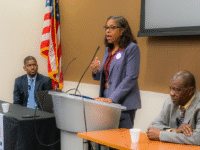

On April 10, 2025, a federal appeals court gave residents of St. James Parish what they’ve been fighting for years to get: their day in court.

In a landmark decision, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a civil rights lawsuit alleging racial discrimination in St. James Parish’s land-use policies can move forward. Filed in 2023 by local faith-based groups including Rise St. James and Inclusive Louisiana, the lawsuit argues that the parish intentionally sited toxic petrochemical plants in Black communities — exposing generations to dangerous pollution while protecting wealthier, whiter areas.

“We have been sounding the alarm for far too long,” said plaintiff Gail LeBoeuf, a lifelong resident currently battling liver cancer. “Too many lives have been lost to cancer.”

Cancer Alley’s Front Lines

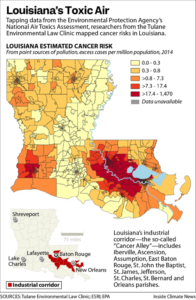

St. James Parish lies in the heart of “Cancer Alley,” an 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River packed with petrochemical plants and oil refineries. The area’s nickname is no exaggeration: federal data shows that Black-majority districts in the parish face cancer risks far exceeding national averages. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has flagged these neighborhoods as among the most toxic in the country.

St. James Parish lies in the heart of “Cancer Alley,” an 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River packed with petrochemical plants and oil refineries. The area’s nickname is no exaggeration: federal data shows that Black-majority districts in the parish face cancer risks far exceeding national averages. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has flagged these neighborhoods as among the most toxic in the country.

Of the 24 industrial facilities operating in St. James by 2019, 20 were in the two majority-Black districts. The lawsuit claims this is no accident — it’s the result of decades of deliberate zoning decisions that have turned Black communities into sacrifice zones.

The 2014 parish land-use plan is central to the case. That plan designated large swaths of Black neighborhoods for “residential/future industrial” use, while placing protective “buffer zones” around white-majority areas and plantation museums. It also made no such provisions for Black churches, schools, or historic sites.

“They’re packing our neighborhoods with plants that produce toxic chemicals,” said Barbara Washington of Inclusive Louisiana. “We all have stories about our health and the health of our friends.”

A Fight for Air — and Ancestry

The lawsuit doesn’t just claim civil rights violations. It also invokes religious liberty, arguing that the parish allowed industry to desecrate the burial grounds of enslaved people. Some facilities, like the proposed $9.4 billion Formosa Plastics plant, were approved on land that contains unmarked slave cemeteries.

“For some of us, St. James Parish is the home of our ancestors, who were slaves,” LeBoeuf said. “Who worked the land for generations and never got paid.”

The lower court initially dismissed the suit on procedural grounds, claiming it was filed too late. But the appeals court disagreed, calling the allegations “replete with discriminatory land use decisions” that continued long after 2014.

“This is a real vindication of their struggle,” said Pamela Spees, attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights. “Now we get to deal with the claims on their merits.”

Science Catches Up to What Residents Already Knew

A recent Johns Hopkins University study found that levels of ethylene oxide — a known carcinogen — in parts of Cancer Alley are up to 20 times higher than industry-reported figures. Using mobile labs to monitor in real-time, researchers found toxic concentrations far exceeding federal safety thresholds. In some cases, levels reached parts per billion instead of the expected parts per trillion — a massive difference with real health consequences.

These findings validated what residents have said for years: that the air in St. James is slowly killing them, and official monitoring has failed them.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan has called for tougher regulations and visited Cancer Alley as part of the agency’s “Journey to Justice” tour. But local enforcement remains weak, and political leaders in Louisiana — including Governor Jeff Landry — have resisted federal oversight. Last year, the state even sued the EPA, accusing it of “overreach.”

Meanwhile, Louisiana continues to greenlight more industrial projects in the area, citing economic growth. Yet residents say the only thing growing is the death toll.

“They say they’re bringing jobs,” said St. James resident Rita Cooper. “But what good are jobs if we’re too sick or dead to work?”

A Legal Path Forward — and a Broader Reckoning

The lawsuit’s revival could be a turning point. If successful, it may force a moratorium on new petrochemical plants, create stricter environmental oversight, and pressure the parish to redesign zoning practices that have long harmed Black communities.

It could also set a national precedent by showing that environmental racism can be challenged under civil rights and religious liberty laws — not just environmental statutes.

“This isn’t just about pollution,” said Spees. “It’s about who gets protected and who gets sacrificed.”

For the residents of St. James, it’s also about survival.

“We’ve been ignored long enough,” said Pastor Harry Joseph. “They can stop a solar farm in a white neighborhood. Why not a toxic plant in ours?”

Outside the courthouse, the community gathered after the court ruling, many with tears in their eyes. LeBoeuf called it “the day the tide started to turn.”

Now, for the first time in a long time, the people of St. James believe justice may finally be within reach.