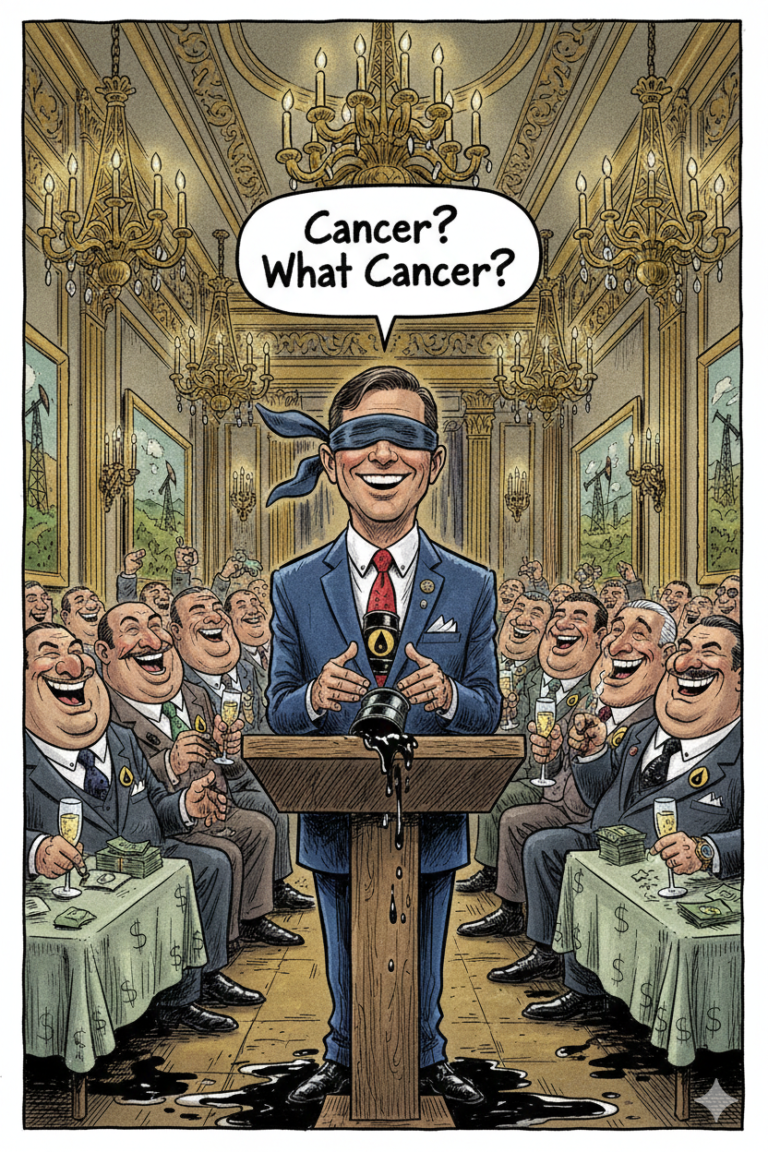

When the CEO of the Louisiana Chemical Association took the Rotary Club podium Wednesday to complain about “misinformation” in discussions of industry health impacts, he stepped so far into cognitive dissonance that it might now qualify as public art.

David Cresson’s defense of the petrochemical industry — the dominant economic engine in the Mississippi River corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans — was a master class in selective reality. Cresson insisted that criticism of the industry is unfair, that cancer rates in the industrial corridor are actually lower than outside it, and that LSU-adjacent job markets somehow inoculate nearby communities against health harm. Setting aside that economic opportunity doesn’t negate air pollution, his argument relies on crude averages rather than the lived experience and emerging science from the communities he purports to defend.

The disconnect becomes especially striking when placed beside cutting-edge research on industrial emissions. A Johns Hopkins University–led study deployed advanced mobile air monitoring in Louisiana’s industrialized corridor and detected ethylene oxide — a proven human carcinogen — at concentrations up to 1,000 times higher than what regulators consider safe. These highly localized real-time measurements, which repeatedly flagged spots far above EPA modeled estimates, illustrate how emissions can be invisible to traditional sampling yet still loom over schools, homes, and fencelines. The researchers found levels of the toxic gas in some places that dwarfed older monitoring data — a discovery that makes parish-wide average cancer rates a terrible proxy for actual exposure risk.

Ethylene oxide isn’t some hypothetical risk at the margins. Scientific consensus treats it as a carcinogen at infinitesimal concentrations, and this study suggests that the air people breathe near industrial complexes isn’t just “industrial,” it’s actively dangerous. That’s not “misinformation”; that’s empirical evidence suggesting regulators and communities dramatically underestimate real exposure.

Cresson’s response — a clumsy refocus on macro statistics — isn’t a defense of science. It’s a rhetorical sleight of hand: redirect attention away from where risk actually clusters so industry can claim victory in aggregated numbers. Meanwhile, the people living directly downwind of emissions don’t get to step outside the parish average.

Environmental advocates, health scientists, and community leaders have made this point for years: cancer and pollution risk in Louisiana isn’t flat, it isn’t evenly distributed, and it isn’t accurately captured by coarse datasets that smooth over blocks, census tracts, or parish lines. Dr. Kim Terrell’s observation that health outcomes vary significantly within parishes isn’t an attempt to sow doubt — it’s a critique of the very analytic framework the industry relies on to dismiss concern. Cresson’s rebuttal, framed as a facts-based “debunking,” instead highlights a willingness to ignore high-resolution environmental health data because it complicates industry’s preferred narrative.

And that’s the real issue: when the CEO of a major industry publicly reframes localized toxic exposure as “misinformation,” he reinforces a broader pattern in which legitimate community health concerns are treated as inconveniences. Underneath the polished “economic benefits” pitch lies an implicit admission that otherwise these issues would stand on their own — because they do.

The good news, from a public accountability perspective, is that new science is emerging that refuses to be so easily dismissed. The bad news is that industry leaders like Cresson are still talking as if finely tuned epidemiology and measured air-to-health linkages don’t exist, relying instead on broad statistical dust-throws. That’s not leadership. It’s damage control — and at this point, disingenuous.